I’ve been toying for a little while with the idea that James Ellroy’s historical fiction might be profitably read as genealogical fiction. I haven’t had the chance to develop this reading properly, as it’s outside the scope of my thesis work so anything longer than a blog post probably counts as procrastination for now.

The idea has become more insistent in light of the way his current project, the ‘new’ LA Quartet, is seeking to tie together his earlier works into a single sequence. At the turn of the millennium, when his historical scope broadened to focus on 1960s North American and global politics with the Underworld USA Trilogy, the novels were accompanied by declarations in interviews that his ambitions had now moved beyond Los Angeles and the conventions of the police procedural genre. However, his most recently published novel, Perfidia, marks the start of a new sequence of novels in which Ellroy returns to 1940s Los Angeles, and the LAPD in particular, with a new ambition – to tie together characters and events from the LA Quartet and the Underworld USA Trilogy into a single, sprawling narrative of the dark side of mid-century US politics.

Ellroy’s historical fiction involves depicting speculative circumstances surrounding actual historical events; hypotheses that, whether we find them credible, compelling or confounding, pose questions about the historical narratives we hold to. The Underworld USA Trilogy begins, in American Tabloid (1995), with this declaration:

It’s time to demythologize an era and build a new myth from the gutter to the stars. It’s time to embrace bad men and the price they paid to secretly define their time. (American Tabloid, prologue)

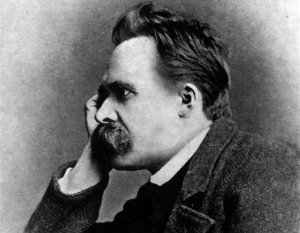

In On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), Friedrich Nietzsche proposed an account of the development of modern moral concepts such as good and evil, posing the challenge of whether we can comfortably hold to such notions if their obscured roots are in attitudes that might make us uncomfortable.

My suspicion is that this genealogical method can explain the divisive quality of Ellroy’s work, whereby despite increasing critical regard, significant writers such as social historian Mike Davis can be particularly scathing about Ellroy’s perceived reactionary tendencies. The genealogical method does not insist ‘This should not have been’; it challenges ‘What does it mean to you that this might have been?’ – and this absence of explicit value judgements can prompt wildly differing responses in the reader.

Looking up something in a much earlier Nietzsche work, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life (1874), I found a passage that could easily serve as an epigraph for Ellroy’s project:

Excellent post. There are some sporadic Nietzsche quotes in Ellroy’s Because the Night and Killer on the Road

LikeLiked by 1 person