It’s becoming clear that one of the central themes of my next thesis chapter will be mobility — or more specifically, the restrictions imposed on the mobility of black Angelenos, and the representation of this immobility in works of fiction and cinema spanning the post-war / mid-century / civil rights eras.

The first chapter of my thesis analyses Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels, and one trope that comes out very strongly there is the importance of Marlowe’s mobility. One critic calls him ‘first motorized private eye in the most thoroughly motorized city in America’ (Fine, 2000), and a consequence of that motorised status is that Marlowe’s investigations are particularly kinetic in nature — that is, they are bound up with movement through time and space, rather than the generally static intellectual deductions of the ‘Golden Age’ detective. Whether pursuing suspects or inspecting crime scenes, Marlowe moves with fluidity across Los Angeles, and between its different districts and social classes (and in doing so, Fredric Jameson suggests, knits together an otherwise fundamentally fragmented social sphere). Marlowe’s mobility is not unproblematic (since he is a private eye rather than a law enforcement official, meaning he exposes himself to the risk of being incriminated through discovering crime scenes and withholding evidence); but it is nevertheless a particularly distinctive and significant aspect of his method.

My most recent chapter, focusing on the Los Angeles police novels of Joseph Wambaugh and James Ellroy, reflects on how the city is divided up into discrete jurisdictions, with different institutions, departments and divisions given responsibility for policing those territories. One distinctive aspect of Ellroy’s fiction (The Big Nowhere in particular) is its exploration of how this process of territorialisation is experienced by those who work within and enforce such jurisdictions. Some exploit the process for their own gain, and to satisfy their own cruel urges, such as principal antagonist Dudley Smith and his vision of ‘containing’ vice ‘south of Jefferson’. Others, such as Sheriff’s Deputy Danny Upshaw, become caught up in the complexity of these jurisdictional networks, transgressing the boundaries within which they are expected to operate, and are tragically punished for it. In other words, even those with official sanction to enforce territorial boundaries encounter restrictions on their mobility, and are exposed to the risk of incrimination.

Having considered figures representing, in some sense, ‘official’ power — licensed private investigators and police officers — a vital perspective currently missing is that of everyday citizens of the city; the people who are subject to the investigations of the private eye, and the law enforcement methods of the LAPD.

South Los Angeles was, for the decades clustered either side of mid-century, home to the vast majority of the city’s African-American community – in large part due to the restrictive covenants that, pre-1948, limited black homeownership to certain areas. When it is depicted in white-authored mid-century fiction at all, South LA often appears in exoticized form, as a threatening underworld populated by grotesque racial caricatures (as in the opening chapters of Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely). My particular interest, in this next chapter, is with works written from the perspective of the people who actually lived around Central Avenue and in Watts; with works that engage with the African-American experience of Los Angeles across the 20th century: Chester Himes’s novel If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945); Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins mysteries (1990-2014); films from the ‘LA Rebellion’ school of filmmakers that came out of UCLA in the late 60s and 70s, including Killer of Sheep (dir. Charles Burnett, 1978) and Bush Mama (dir. Haile Gerima, 1979).

If one definition (one of the very earliest, in fact) of film noir is works that show us the ‘criminal perspective’, then my concern here is with an ambiguous type of noir – the perspective of those who are not criminals, but are treated as such; those who are constantly alive to the possibility that they may be falsely accused of a crime, and who may be unable to provide a satisfactory alibi in the face of such racially biased networks and structures of power. It is, I suppose, about stories told from the criminalised perspective.

Throughout the texts I’ll be analysing in more depth during this next chapter, there are examples of black protagonists dealing with challenges to their mobility – with obstacles, restrictions and the temptation of stasis. Bob’s morning commute to his job at the shipyards in the second chapter of If He Hollers… is a fraught drive in which every red light and obstructive white pedestrian frays his nerves further. The experience exacerbates the anxious state into which he wakes in the opening pages of the novel, which Bob describes as ‘Living every day scared, walled in, locked up’. Later, it is only the thought of losing his car that will stop him striking his department superintendent after he is unfairly demoted: ‘My car was proof of something to me, a symbol. But at the time I didn’t analyse the feeling; I just knew I couldn’t lose my car even if I lost my job.’

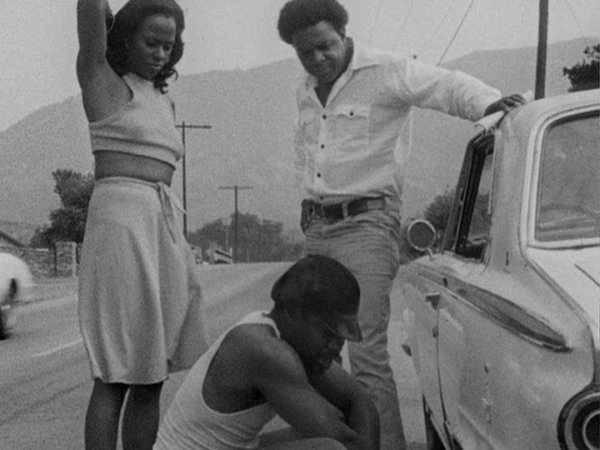

Killer of Sheep opens with children playing beside railway tracks, ineffectually throwing stones at the passing freight cars as they speed through Watts without stopping. The film as a whole is preoccupied with stasis, inertia and failed movement, particularly in relation to cars: from the attempted road trip out to the country that is halted by a flat tyre, to the car engine that Stan barters for and loads onto a truck, only for it to be jolted onto the tarmac and damaged beyond repair the moment he tries to set off. Where Himes’s protagonist Bob is raw with anxiety and drawn towards violence, in Killer of Sheep Stan is seemingly gripped by depression or despair – emotionally withdrawn from his wife and confined by some spiritual inertia.

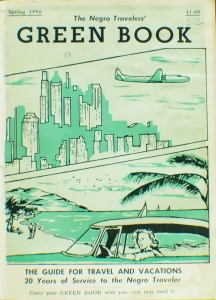

It is with these images in my head that I first learned about ‘The Negro Motorist Green Book’. The ‘Green Book’ was a guide for African-Americans travelling in the US (and eventually further afield), published between 1936 and 1966. This was a period, of course, in which the country was in the continuing grip of Jim Crow; in which not just individual establishments but whole towns could designate themselves ‘whites only’. Despite a degree of increased social and geographic mobility amongst the black middle class, cross-country travel still involved uncertainty and the threat of violence, and required careful planning. The ‘Green Book’ listed, state by state, facilities that were known to welcome African-American business and leisure travellers, including restaurants, bars, hotels and service stations.

That there was the need for such a guide (and for three decades) powerfully emphasises how the imagery and metaphors traditionally attached to automotive travel in mid-century America – the car as a symbol of individual freedom, the limitless highway offering opportunity and escape – were in practice images of the white American experience. African-American travellers, in contrast, had to confront not just inconveniences but potentially fatal restrictions on their mobility. The centrality of the automobile to Los Angeles life – and the disempowerment entailed by its absence – is a cliche in fictions of the city (from Sunset Boulevard, to Chinatown, to Greenberg). The very existence of the ‘Green Book’ also gives historical context to the images of restricted movement found in the likes of Killer of Sheep and If He Hollers Let Him Go; it emphasises to us that whilst the trauma attached to being deprived of a car is a perennial LA concern, in Watts and around Central Avenue the stakes of mobility were a great deal higher.

[…] One of the most significant combinations is that of space and time in motion, since movement entails both the passing of time and the passing through of space. Disorientation involving movement can in turn take multiple forms, from instances of unnaturally fast or irregular movement, to enforced stasis and the psychological consequences that can result. […]

LikeLike

[…] is no less mobile, and no less motorised, than Chandler’s private eye. I’ve posted before about how Bob’s car ownership is central to his own sense of status and identity. And he easily travels an equivalent distance in If He Hollers… (1945) to Marlowe in The High […]

LikeLike