Two-thirds of the way through Perfidia, something else that feels very Underworld USA rather than L.A. Quartet about the novel is the shifting relationships and loyalties between the POV characters. In both The Big Nowhere and L.A. Confidential the protagonists begin with different, potentially conflicting aims (in the case of Bud White and Ed Exley, outright antagonism). But in both cases this resolves into some form of collaboration – towards resolving the central case, and in opposition to Dudley Smith. (It’s not a total resolution of differences, but it’s a sufficient one.)

In the trilogy, loyalties and aims shift from chapter to chapter – compromise, greed, outright betrayal. Above all what we see is change – individuals responding to circumstances, forming new alliances, betraying old ideals; not as a binary shift from was to is, but as an extended series. And each series intersects with those of the other protagonists, forming a complex network. (We might even be inclined to call it rhizomatic…) This of course influences our attitude to the characters – because they are less stable, their desires more complex, they resist identification (despite the fact, rather perversely, that they are perhaps more ‘realistic’ characters as a result).

Dave Klein’s role as a bridge between the quartet and the trilogy becomes more clear in these terms. As he is the sole POV character in White Jazz, we do not experience the same alternation of perspective and constantly shifting pragmatics as in the trilogy. But Klein’s particular status – playing sides off against each other, out for himself and reacting to the new opportunities as they arise – definitely foreshadows the trilogy.

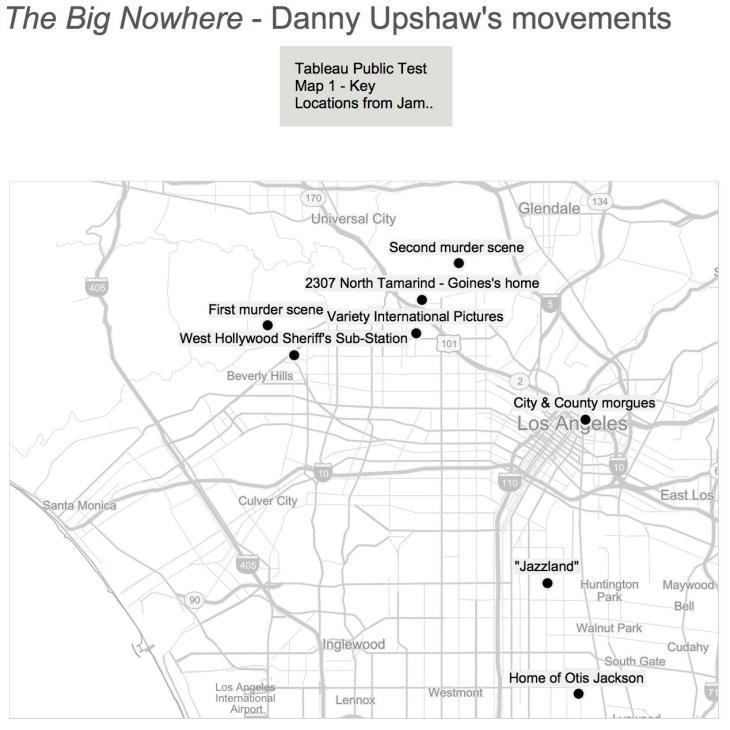

Perfidia is definitely closer to the trilogy than the quartet in this regard. Characters calculate and compartmentalise, chapter to chapter. Ashida shifts from Parker to Smith (and surely away from Smith again at some point…), has an odd bond with Kay – and we’re still not sure what he ultimately wants – or if he is simply attempting to survive, to make himself useful. (A side note: Ashida feels, in the early part of the novel, like a sympathetic character – something at least partially prompted by what he has in common with Danny Upshaw from The Big Nowhere – forensic aptitude, repressed homosexuality. But I’m starting to suspect that this may be a feint from Ellroy…). Kay’s shifts are wilful, sometimes perverse – her desire is simply to Act, to be able to influence the course of events. Parker is, particularly in the middle section of the novel, a mess – lapsing back into alcoholism, not acting in his own best interests. We know, of course, that Parker will ‘succeed’ – that he will become Chief of Police, and will reshape the department. So is this an aberration, brought about in part by the chaos of war? An experience that will further motivate and shape his later success? Or (knowing Ellroy) will we in later novels see the extent to which Parker’s historical success is actually compromised – manipulated at least in part, perhaps, by Dudley Smith.

Interestingly, Dudley Smith, as he pieces together details of Parker’s operation to infiltrate the Hollywood communist cell around Claire de Haven, interprets it as Parker stubbornly involving himself in a misguided ideological crusade. But this picture of Parker – rigid, idealist-to-a-fault, the ‘historic’ view of William H. Parker – doesn’t seem to fit with the Parker we actually follow during the novel. There, the operation appears to be ideologically inspired but quickly gives way to voyeurism, and to the satisfaction of wielding power for its own sake (sadism even?). Smith himself is the most acutely pragmatic character, the most comfortable with these rhizomatic networks of power, compromise and influence. As he terms it, in an opium haze: Thought and Act. The question is to what extent we are going to see Dudley at all wrong-footed or compromised himself in the final third of the novel. His relationship with Bette Davis clearly opens him up to some degree of vulnerability; the armoured-car robbery he masterminded is being investigated, and Meeks in particular is antagonistic. But we know it will only ever be a minor set-back, because we know that Dudley’s fundamental power will be consolidated by the time we get to the quartet (although – Dudley is still consolidating over the course of the quartet, to some extent, and he is already influential within the department, and the city, in Perfidia. Is there necessarily some misstep to account for his relatively slow progress between Perfidia and the quartet?)

An important difference between Perfida and the trilogy is the timespan – the former covers a span of weeks rather than years. Of course, this is partially a practical issue – if Ellroy wants to fit three or four new novels into the period between WWII and The Black Dahlia, he can’t necessarily range as freely across the years in each novel. But then again, that could be addressed in any number of other ways: the new books could contain parallel rather than sequential plots (indeed, they still might); he could have begun earlier, with Bill Parker’s exploits as right-hand man to Two-Gun Davis pre-war, and Dudley Smith’s earlier rise. The compressed time-span is certainly appropriate to the circumstances of the plot – the feverish quality of post-Pearl Harbor LA, characters repeatedly mentioning that they can’t sleep, haven’t slept. Historical circumstances compressing time; disorientation…